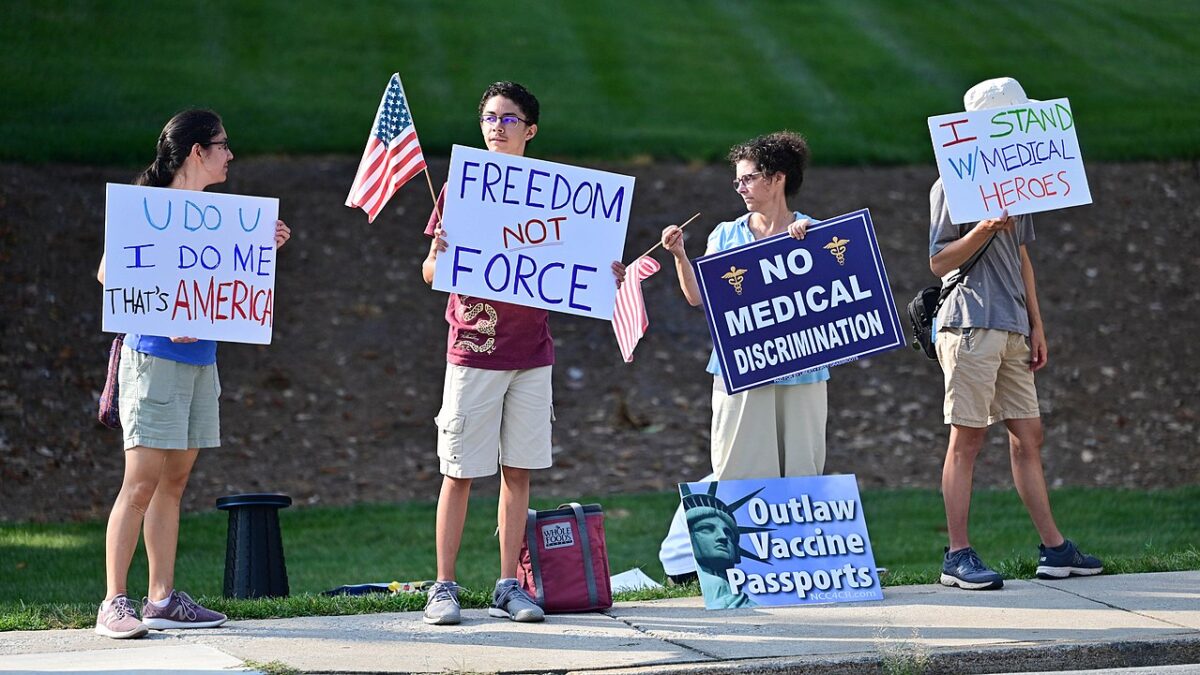

What began as a movement against Covid vaccine mandates has evolved into a broader campaign for health and medical autonomy across the U.S., encapsulated by the slogan “Make America Healthy Again.”

Voters from both political sides are uniting to resist issues like mandated childhood vaccinations and food additives. The “MAHA” movement draws participants from both the natural remedy advocates typically linked to the left and the libertarian-minded individuals often associated with the right.

Health and safety concerns transcend political divides; issues like poor health and addiction affect everyone regardless of their political stance. However, mainstream media often dismisses this unity as “fringe” or “Republican.”

For instance, a recent New York Times article framed this growing resistance as a niche of Republican politics, despite it reflecting the views of many Americans disillusioned by a healthcare system that prioritizes profit over wellness.

Voices against what some label America’s “sick care system”—characterized by a cycle of poor nutrition and reliance on pharmaceuticals—are not marginal; they represent a significant segment of the population frustrated by a dominant narrative enforced by a select group of experts.

Similar to other contentious issues, the more populist Republican Party appears to be the only one offering a platform for these concerns. In September, Sen. Ron Johnson hosted a roundtable titled “American Health and Nutrition: A Second Opinion,” featuring prominent health experts who testified about the concerning state of national well-being.

The response from left-leaning media was immediate and harsh. The day after the roundtable, The Atlantic’s Elaine Godfrey dismissed it as a “Woo Woo Caucus,” putting “health and nutrition” in quotes as if they were mere fantasies.

A board-certified oncologist and gastrointestinal surgeon from Johns Hopkins hardly seems “woo-woo,” nor does a desire to understand what’s in our medicine and food supply.

Godfrey’s commentary echoed the propaganda-style reporting during Covid, which disparaged those wanting more information about vaccines, implying the roundtable had a “do-your-own-research vibe.”

Ironically, the left and the Democratic Party once championed individuals researching alternative health practices and holistic healing, like herbal remedies and nutrition. Many attendees at Johnson’s panel hailed from California, a state often seen as a hub for such ideas.

However, the left has shifted, now aligning with bureaucratic partnerships typical of the right. This health movement reflects a broader resistance against corporate influence in government and an authoritarian media that stifles dissenting views.

While Donald Trump and RFK Jr. represent this emerging Republican faction, new health PACs are poised to sustain its momentum beyond the upcoming elections.

At least two PACs have emerged to rally the united MAGA-MAHA movement. One, the MAHA Alliance, clearly states its goal of securing a victory for Donald Trump in November, which would also elevate RFK Jr. to a significant role, appealing to independent voters.

The other PAC, called Make America Healthy Again, seeks to “dismantle the corporate stranglehold on our government agencies,” which it argues has contributed to widespread chronic diseases, environmental harm, and public distrust.

“The idea of what political party you were before never crossed our minds,” Jeff Hutt, a former Robert F. Kennedy Jr. campaign staffer and now the advocacy and outreach director for the MAHA PAC, told me. “It was this menagerie of the populist political spectrum. It was great to see people who maybe in the past had been divided into team red and team blue — now they were just on team America.”

Hutt’s remarks suggest that the upcoming election is less about the typical Republican versus Democrat divide and more about a conflict between those opposing a nation governed by a federal bureaucracy of biased “experts” and those seeking to maintain that control for their political and financial interests. This includes major agencies that influence health and nutrition, such as the Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Department of Agriculture.

“The idea of a political movement that rejects expertise and prioritizes personal choice in an epidemic is deeply troubling to public health experts, who worry that public health powers will be curtailed if Mr. Trump wins in November,” wrote Stolberg in The New York Times.

The new health movement does not dismiss expertise; rather, it challenges one-sided health perspectives and the vilification of well-qualified experts who diverge from the official narrative of the Democratic regime. This includes figures like Dr. Casey Means, a Stanford-trained head and neck surgeon; Dr. Peter McCullough, a prominent public health expert with over 1,000 peer-reviewed publications and 660 citations in the National Library of Medicine; and Dr. Robert Redfield, former head of the CDC.

The New York Times is correct in noting that this coordinated effort to transform how Americans view health has gained significant traction in Republican politics and has the potential to exert real influence in Washington. Ultimately, this shift could benefit the country.