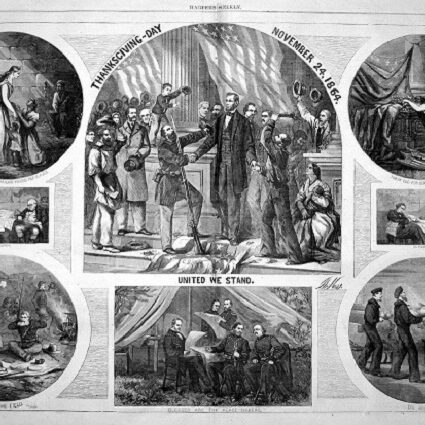

On November 24, 1864, Union Lieutenant Samuel Nichols of the 37th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers prepared to observe the nation’s first official Thanksgiving Day, established as a national celebration on the fourth Thursday of November by President Lincoln.

The morning, Nichols wrote, “dawned beautifully upon civilians and soldiers. Starting wildly from our slumbers at the unearthly sound of ‘Reveille’…we found ourselves with an appetite adequate for the occasion and fully equal to that usually demanded on that auspicious and chicken-stuffed day.”

Still encamped in Winchester, Virginia—where his regiment had played a key role in securing a Union victory and capturing the town just two months earlier—Lt. Nichols appreciated the relative calm of their current duties. Yet, as a seasoned soldier, he understood the fleeting nature of peace. Combat veterans know all too well how the quiet of a crisp November morning can be abruptly shattered by the unpredictability of war.

Most of the regiment, Nichols recalled, chose to skip breakfast to save their appetites for the highly anticipated Thanksgiving feast. However, Nichols, accustomed to having meals disrupted by sudden orders, decided not to wait until the scheduled dinner at 2:00 p.m. “At one o’clock, therefore, I dined in company with three of my companions. We all ate a sufficiency and had a good time,” he noted.

His instincts proved correct. Just as he finished his meal, the regiment was ordered to be “in readiness to move at a moment’s notice.” Within ten minutes, they were marching at a quick pace. By 6:00 p.m., they reached their destination, only to be ordered to countermarch back to Winchester. The column returned to their bivouac around 9:00 p.m., leaving many soldiers disappointed as Thanksgiving passed with neither meal nor celebration.

Such is the nature of army life, as any veteran will attest. Beyond the grinding routines and long stretches of stifling boredom punctuated by the horrors of front-line combat, perhaps the greatest sacrifice of military service—aside from risking life and limb—is enduring separation from loved ones during extended deployments. This absence is felt most keenly during holidays like Thanksgiving, when even troops far from combat zones are acutely aware of missing irreplaceable moments with family and friends.

Still, Nichols’ regiment was fortunate, even if most of them didn’t share their lieutenant’s foresight. While some soldiers missed out on a hearty meal, they were spared the hardships endured 80 years later by their U.S. Army successors entrenched in the frigid, shell-ravaged Hürtgen Forest. For the soldiers of the 121st Infantry Regiment, 8th Infantry Division, Thanksgiving Day 1944 would be remembered not for comfort but for tragedy—a consequence of the high command’s misguided attempt to bring a touch of home to men in foxholes.

Positioned at the very tip of the U.S. advance, the regiment faced the relentless resistance of German defenders deeply entrenched in the forest’s dense foliage and frozen ravines. As 1st Lt. Boesch huddled in his foxhole, the phone rang with an unexpected message from headquarters. On the other end was a cheerful staff officer from the rear, who exclaimed, “Happy Thanksgiving! We’ve got a hot turkey dinner here for every man in the outfit.” The officer assured Boesch that the food was en route to his company.

Boesch couldn’t believe it. “Are you guys nuts?” he said with incredulity. “It’s almost dark and my carrying parties have already made the trip up the hill with rations and water. I can’t send them up there again. Besides, they can’t feed a hot meal in the positions they’re in now. Good God, they’re right on top of the Jerries!”

Those were the orders, the staff officer said. And didn’t the men want a nice taste of home? Boesch shook his head in frustration before screaming into the handset, “I want to see them get three hot meals a day and a dry bed every night and a babe to sleep with, but let’s save the turkey until they can pull back where they can enjoy it!”

Despite raising concerns to the battalion commander that gathering for the Thanksgiving meal could cost lives by making the men easy targets for German artillery, the orders remained unchanged. Hot turkey dinners were delivered directly to the front lines. The soldiers tasked with the deliveries relied on the cover of approaching darkness, but they were still within clear view of the enemy.

As Lt. Boesch had feared, German artillery and mortar fire soon targeted the exposed GIs, who had clustered around the turkey canisters to eat. The barrage resulted in significant casualties, leaving many dead and even more wounded.

Years later, in 1978, retired Major William Freeman of the 121st Infantry recounted the event to General Jim Gavin during an interview. Gavin, reflecting on his time as a young general, admitted that the high command had little understanding of the conditions the GIs faced in the Hürtgen Forest. Freeman shared how the well-intentioned but poorly executed gesture from leadership had led to such a tragic outcome.

“Jerry turned all hell loose! Branded in my mind is position after position with men torn to shreds around busted up turkey canisters—as many as ten in one place.”

In the same letter, Freeman seeks to unburden himself.

“Hindsight says I could have stalled off the dinner and I doubt that the higher echelons would have known about it—but I didn’t. Granted that greater control could have been used all down the line… but dangle hot turkey to men in a cold, wet forest, that have had nothing but K rations, and it’s not that easy to keep them from bunching…

“For many, many years after the war I would go to one of my relations for Thanksgiving dinner, and before I could touch a bite I would get up and go to the back yard and cry like a baby, I passed up a helluva lot of turkey dinners.”

Two American regiments, two wars, two enemies, two Thanksgivings—united by the same sacrifice for their country and for one another. As the holiday season begins, let us pause to honor those who stand watch, ensuring we can gather in safety, free from harm.

Happy Thanksgiving to all who serve in dangerous and distant places. We are deeply grateful for you.